Leprosy

About leprosy

Leprosy (also known as Hansen’s Disease) is a chronic neglected tropical disease associated with poverty. It is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. Leprosy symptoms can take 20 years or more to occur. Leprosy infection damages the peripheral nerves in the skin’s surface, resulting in loss of sensation. Without the feedback of pain, sufferers more easily damage their hands and feet with burns and ulcers. The nerve damage can then grow to elbows, wrists, knees and ankles and, if not treated, eventually lead to limb deformities, paralysis and limb loss, as well as blindness. However, leprosy is treatable with antibiotics and, if caught early, can be cured and these serious issues avoided.

Over 120,000 new cases of leprosy are diagnosed every year – this is one every two minutes - however, leprosy is likely to be under-reported due to its stigma and link to those living in poverty. It is estimated that around three million people worldwide are living with irreversible damage caused by leprosy.

Leprosy can have a profound effect on those infected as they often also suffer from severe social stigma and discrimination, loneliness and isolation – fear and misunderstanding of the disease means that, even today, sometimes the sufferer’s whole family can be ostracised. Worldwide, 146 laws are still in place that discriminate against people affected by leprosy, including some that segregate and isolate people from their communities and even their families.

Where is leprosy found?

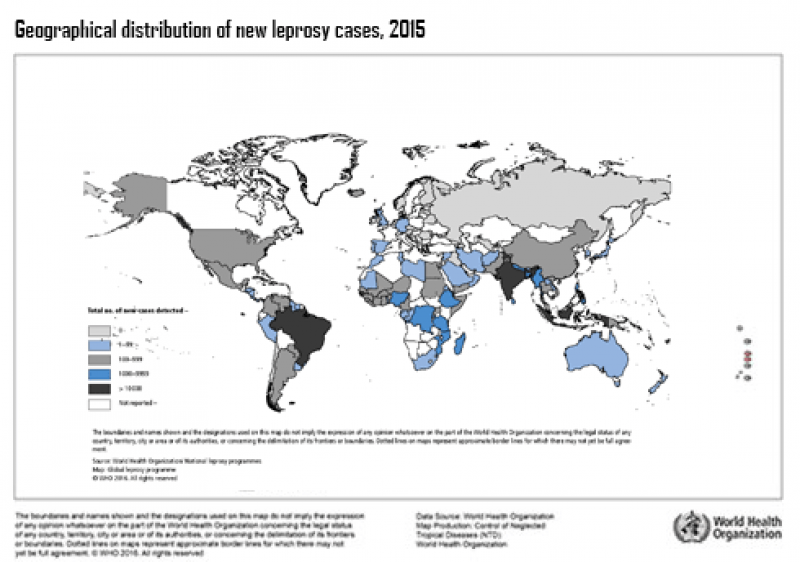

Historically, leprosy was found worldwide; today it is mainly found in 14 countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, DR Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Philipppines, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. More than half of all leprosy cases are diagnosed in India.

How is leprosy spread?

Leprosy is only mildly infectious. How a person acquires Mycobacterium leprae and develops the disease remains uncertain, although it is currently thought likely that it is spread when healthy individuals inhale water droplets coughed or sneezed by infected people. Prolonged, close contact with someone suffering from leprosy is needed to catch the disease, and more than 95% of people have natural immunity to the disease.

Currently, leprosy has to be diagnosed using clinical symptoms as there is no diagnostic laboratory screening test.

Is leprosy curable?

Leprosy is curable with antibiotic treatment for 6-12 months. Unfortunately, for many people living in poverty around the world, diagnosis is too late to avoid limb damage or blindness, and the stigma associated with these injuries and a leprosy diagnosis.

Vaccines against leprosy

There is currently no vaccine specifically for leprosy. BCG was developed as a vaccine against tuberculosis (TB), and it also affords some protection against leprosy because Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae are highly related. However, BCG is protective against leprosy to very varying degrees and only in some populations, and even where protection is observed it drops off over time. Leprosy remains endemic in some countries where BCG vaccination is widespread, so we clearly need to improve on BCG.

There are few leprosy vaccines in development, although three are currently in Phase 3 clinical trials which means they have shown promise and are now being tested on a large scale in many hundreds of subjects.

A successful leprosy vaccine would be a critical step in controlling the epidemic by preventing disease and transmission, and could be used in conjunction with other strategies, including better diagnostics, increased awareness, and the development of new drugs, to finally eradicate this disease.

How is VALIDATE helping?

At the VALIDATE Network, by bringing together leprosy researchers from around the world we hope to speed up progress towards an improved vaccine against this neglected disease.

Further information (find more on our Publications page)

How leprosy affects the body and the impact it can have on a person’s life – The Leprosy Mission

CDC Hansen's Disease webpage

International Leprosy Foundation (ILEP) Zero Discrimination campaign

Mycobacterium leprae

Mycobacterium leprae is an acid-fast, rod-shaped bacillus and is an intracellular pathogen causing leprosy in humans and armadillos. The genus Mycobacterium, also contains M.tuberculosis which causes TB (tuberculosis).

The challenges of developing a leprosy vaccine

Developing an effective vaccine against leprosy has proved challenging over the last decades. Mycobacterium leprae is an intracellular pathogen, which means it can ‘hide’ from the immune system inside our body's cells, which can make vaccine development more tricky. As is the case for TB as well as leprosy, we don’t understand which parts of the human immune system are important in protection from these infections, which makes it difficult to design a vaccine because we don’t know what it needs to do to be effective. It’s also unclear why BCG is effective against leprosy (and TB) in some populations and not others, and we don’t want a new vaccine to be subject to the same pitfalls.

M. leprae is notoriously difficult to work with in the lab, as it cannot be cultured in artificial medium (so making large amounts of vaccines based on M. leprae itself is challenging), and the only animal models available are nine-banded armadillos and mouse footpads. Funding is also a huge challenge; leprosy numbers are decreasing as sanitation and general health improve worldwide, meaning funders are less interested in funding research - but leprosy cases are likely underreported and unlikely to drop to zero without a vaccine. In addition, as leprosy is a disease not generally found in the developed world and therefore unlikely to make a profit for its developer or manufacturer, it is difficult to encourage large pharma and industry organisations to work on leprosy vaccine development.

How is VALIDATE helping?

By bringing together researchers working on different (but similar) pathogens, discoveries in one field can be more quickly applied to research against another pathogen. Bringing together researchers from different disciplines and institutes in new collaborations means knowledge can be exchanged and new research ideas for the field can be generated and investigated. VALIDATE can provide invaluable funding for neglected disease vaccine research. Finally, bringing new researchers into this field, and progressing the careers of early career researchers, will aid with new ideas and the continuation of the field into the future.

Further reading

Coppola M et al 2018. Vaccines for Leprosy and Tuberculosis: Opportunities for Shared Research, Development, and Application. Frontiers in Immunology 9:308

Duthie MS et al 2020. A phase 1 antigen dose escalation trial to evaluate safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of the leprosy vaccine candidate LepVax (LEP-F1 + GLA-SE) in healthy adults. Vaccine 38(7):1700-1707.

Bezerra-Santos M et al 2018. Mycobacterium leprae Recombinant Antigen Induces High Expression of Multifunction T Lymphocytes and Is Promising as a Specific Vaccine for Leprosy. Frontiers in Immunology

Characterising the BCG-induced antibody response to inform the design of improved vaccines against M.tuberculosis, M.leprae and M.bovis

Dr Rachel Tanner (University of Oxford, UK) - VALIDATE Fellowship

Read more here

Video: A Vaccine for Leprosy

https://www.youtube.com/embed/1fzDWmAc2YY

In this video, Dr Hua Wang talks about leprosy, how it can be tackled and what VALIDATE is doing to develop vaccines to help eradicate the disease.